The Encyclopaedia: S-Z

| St Mary's Hospital Chichester: | Awaiting entry |

|---|---|

| Scantling: | The dimensions of a timber in section. In the literature the term is usually applied to timbers of smaller section like common rafters. |

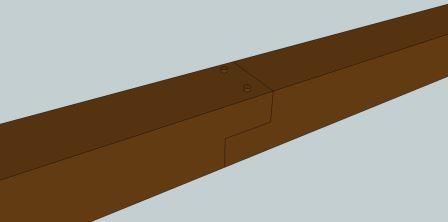

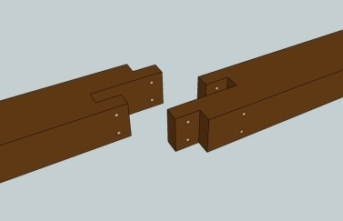

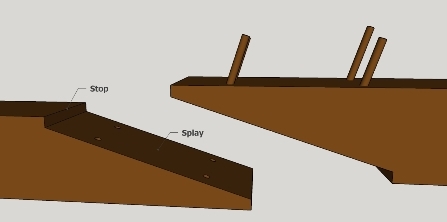

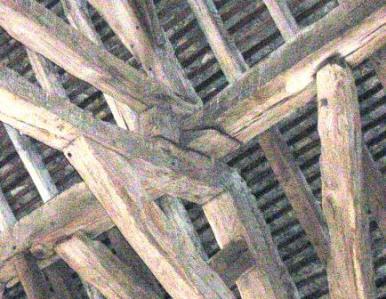

| Scarf: | Joint used to connect timbers longitudinally, most often found in purlins, wall plates and sills. Scarfs vary enormously in complexity, and some of the extremely elaborate examples seem over-engineered. Often located in obscure parts of a structure and going unobserved unless you are looking for them - was this the carpenter simply revelling in his skill? The names given to these joints - where adjective is piled upon adjective - become equally complex. Best perhaps to see the illustrations below (not forgetting the scissor scarf found in a rafter in Lincoln Cathedral).

Literature: Brunskill (2007); Alcock et al (1996); Hewett (1985 & 1997). |

Right: A refinement of left: side-halved and bridled, in a wall plate (the tenons are just visible).

Right: Apologies for the photo, but it serves to show that the C14 carpenter of Middle Littleton Tithe Barn (Worcs) thought that cutting a stop to the splayed scarf in his plate/purlin was not worth the bother.

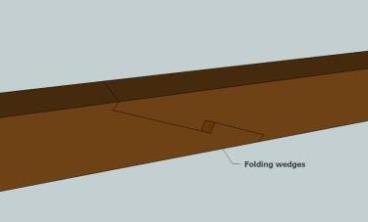

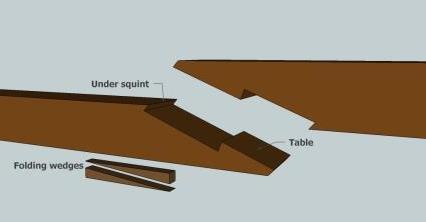

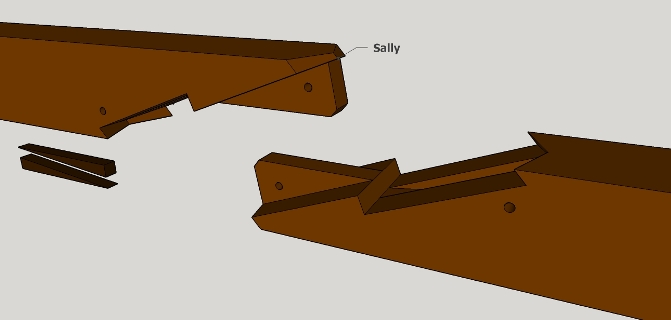

Folding wedges or a solid wooden key were driven between the tables to force the ends of the joint against their stops - in this case under-squinted as an extra safeguard to prevent the joint springing apart. A challenge to mark out and cut.

The zenith of of scarfing techniques: Stop-splayed and tabled, with under-squinted and sallied (protruding) abutments and internal tenons. Belt & braces they may be - but are the internal tenons structural overkill?

Cecil Hewett found an example in the wall plate of a house in Herts. which he dated to 1295. And the carpenter there went even further and drove pegs down through the splays. One can imagine him standing back and dusting off his hands: 'now that'll never come apart.'

| Scissor Bracing | awaiting entry |

|---|---|

| Single-Framed Roof | Roof constructed without principal trusses; purlins framed to principals are absent. Compare double-framed roof. |

| Sole Piece | Horizontal timber in rafter foot |

|---|---|

| Soulace: | Strut, connecting a common rafter to the underside of a collar. Referred to in medieval documents (with a variety of spellings) as 'sous-laces' - roughly translated from French as 'under ties'. The soulace helps to manage lateral wind forces. awaiting illustration |

| Stud: | Relatively lightweight vertical timber in a wall. |

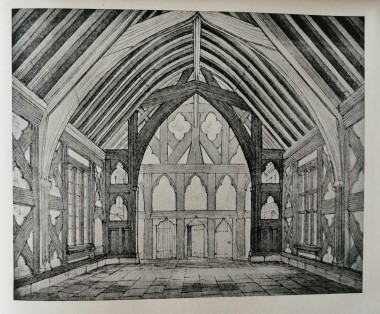

| Spere Truss | Timber-framed transverse partition incorporated into the main structure of a later medieval hall. Located at the 'low' end of the hall, it served to divide, and to some extent screen ('spere'), the lordly space from the domestic service passage with its external door(s). Mundane comings and goings would thus be mitigated, as might draughts.

Literature: Crossley (1951); Wood (1983). |

Drawing from Crossley.

| Stokesay Castle

Great Hall (1254-1290d) | Awaiting entry

Literature: |

|---|---|

| Summer: | 'The carpenter or wright hath layde the summer bemys from wall to wall and the ioystis a crosse.' William Horman (1519).

In a building of more than one storey, a beam carrying the timbers of the upper floor. Sadly, the term is not found some dictionaries, who prefer less romantically, but with some justification, 'girding beam' or 'girt'. Summers are mentioned (the term applied loosely) in medieval documents, in which they are also called 'dormants', this word perhaps the source of the modern 'sleepers.' Illustration here Literature: Salzman (1952).

|

| Tie Beam: | Transverse timber, usually of heavy section, connecting the walls. When framed securely into roof timbers it removes the problem of lateral thrust. See illustration

Below, a fine medieval tie-beam roof: the Monks Dormitory, Durham Cathedral, carpentered by Ellis Harpour between 1398 and 1404. |

|

Span: I was shown a document stating that the dormitory is 39ft (11.9m) wide. I must admit I thought it looked wider. I didn't have my laser rangefinder with me, so I paced it out, and it looked to be around 44ft (13.4m), but maybe my step is getting shorter with age...

I am awaiting confirmation of the span, but in any case, at around 39ft this is wide for a medieval clear-span structure (no aisle posts or hammer beams to provide support). The nature of woodland management and increasing demand meant that long timbers of heavy section became more difficult to find during the middle ages. (See under William Hurley for an example of this). So the width of most manorial halls, for example, was kept to around 30ft (9.1m) or less. Even halls for the loftiest of clients weren't much wider: Stokesay Castle, Shrops. (1254-1290d), c. 30ft (9.1m). Penshurst Place, Kent (c. 1341), for London property speculator and money lender (plus ça change) Sir John Pulteney, 39ft. Dartington Hall, Devon (c. 1388-99), for Richard II’s half-brother, 37ft 6in (11.4m) Great Hall, Bishop of Winchester's residence, East Meon, Hants (1395-97), 26ft (7.93m). Great Hall, Lambeth Palace (probably late c14), 28ft (8.5m). Eltham Palace (1470s) c. 36ft (11m). There are no roof 'trusses' in his shallow-pitched roof. It has no principal rafters - there's hardly room for them. Instead stubby king and queen posts support the ridge and purlins. Long and slender arch braces (was this slenderness a shortage of timber, or an aesthetic choice?) strut the twenty-one tie beams. Thus, only around half the length of the tie beam is left unsupported. Interestingly, Ellis chose to use tension struts to secure the the arch braces to the wall posts. These are framed with dovetailed lap joints, so Ellis must have thought the arch braces in danger of bellying out. Maybe it was an afterthought. Or maybe they are aesthetic—some have a nice curve. Even more curious are the box ties fitted to the tie beams of the ten most southerly frames. They are meant to provide structural insurance to the tie beam-to-arch brace framing. But why? Arch braces are normally thought to function under compression. Did somebody (maybe the replacement master mason appointed in 1402) think the tie beam was likely to shrink away and the joint to pop apart? Surely the tie beam was more likely to sag. Or perhaps the box ties too are decorative. Odd. Thanks to the very helpful cathedral guides during my visit there. Update 05.09.24: One of the cathedral guides has very kindly informed me that he measured the span with a rangefinder and it came out at around thirty-seven and a half feet (11.4m). But the plot thickens. I finally managed to dig out my copy of Engineering a Cathedral, which I knew was mainly about Durham. In there is a fairly esoteric article about the dormitory roof written by a structural engineer. He gives the span as 40ft (12.3m). Whatever the case, this is an unusually wide medieval roof! Literature: Jacques Heyman, 'The Roof of the Monk's Dormitory, Durham', in Engineering a Cathedral, ed. Jackson (1993).

|

Right: As the tree tapered he ran out of log to square off. You can still see the form of the tree. See also the scarf joint below.

Right: A scarf joint. So Ellis ran out of long-enough beams at this point—or it is a later repair? The joint, however, appears to be of the keyed and tabled type. It would be unusual for a post-medieval carpenter to use this type of joint. The iron strap is likely post-medieval.

| Wall Plate: | Horizontal timber or timbers running along the top of a timber or masonry wall which receives the ends of the rafters and/or tie beams. See Reversed Assembly and Principal Frame. An account from 1346 refers to a house in Westminster constructed with 'a piece of timber called plate, 20ft long and 3ft broad, lying in the wall under the roof, on which various beams are set and fixed.' It seems unlikely that this was a single timber 3ft broad (see 'Woodlands'), but probably a double or triple wall plate composed of narrower timbers.

Literature: Salzman (1952)

|

|---|

| Westminster Hall: | Hammer-beam roof; Hugh Herland; completed probably 1398.

Technically audacious, unprecedented and unparalleled visually, the greatest work of English medieval carpentry. The colossal royal hall of William Rufus (comp. 1099) had stood for nearly three centuries on Thorney Island, west along the strand from the City of London, when in the early 1390s Richard II decided to erase its by then passé design. The form of the eleventh-century carpentry is unknown. Recent academics have forcefully argued for a boarded, scarfed tie-beam roof. But it may well have been of aisled construction, of arcade posts, arcade plates and common rafters. This was a type of structure (the arcade posts sometimes substituted by stone piers) that was to persist in high-status halls soon after the completion of Rufus’s hall and for the following two-and-a-half centuries (for examples: the royal house at Cheddar (early C12); Leicester Castle (c. 1150); Farnham Castle (mid C12); the Bishop’s Palace, Hereford (1179); Henry II’s great hall at Clarendon (c. 1181); Oakham Castle, Rutland (1180-90); the hall at Winchester Castle (early C13)). But by the beginning of the fourteenth century taste in seigneurial and royal halls had moved on. Wealthy patrons had developed a liking for the open hall, uncluttered by aisle posts. Examples of this trend for the elimination of aisle posts are: the great hall of the Archbishop of Canterbury’s palace at Mayfield, East Sussex (c. 1330); Penshurst Place, Kent (c. 1341) constructed for the London merchant and financier Sir John Pultenay; the great hall at Windsor Castle built for Edward III (c. 1362); and probably the great hall of Kenilworth Castle, Warwickshire, constructed for John of Gaunt in the 1380s. For a hall designed to display his divinely ordained regality, King Richard II would demand the apotheosis of any new architectural trends and technical advances. But how was 'the disposer of the King’s works touching the art or mystery of carpentry', Hugh Herland, supposed to manage the vast span of Westminster Hall of nearly 69ft (21m) without any supportive aisle posts? In considering the challenge of the widest span of any English medieval structure, Herland must have dismissed a number of options early on. Oak tie beams of a double-framed roof at around seventy-five feet in length (to allow them to sit securely on the wall head), each weighing approximately twelve tons, would have been impossible to source, constructionally inconvenient and - eliminating any prospect of soaring verticality to the roof - aesthetically unthinkable. Crucks, including base-crucks, of such massive dimensions would similarly be impossible to locate, and besides, full crucks perhaps smacked of the bucolic. An arch-braced roof is an attractive open roof form, and was being used to enrich fourteenth-century buildings of prestige. But arch-braced trusses are inherently poor at resisting lateral thrust, and to span the enormous space at Westminster with such a structure would be unconscionably risky. The hammer-beam roof was Herland’s only option: hammer-beam construction supplies aesthetic possibilities not found in other frames; it is a form of structure which inherently uses shorter timbers, thus avoiding timber supply problems; and, as a system of buttressed opposing brackets, it offers a degree of structural stability.

In Cescinsky & Gribble (1922). Hugh Herland’s singular roof at Westminster has triggered lengthy debates and heated arguments. Antiquarian interest began in the early nineteenth century, and investigations, archaeological, technical and art-historical continued well into the twentieth. Debate has largely centred on how the roof performs structurally, with the function of the dominant - and extraordinary - arched rib the focus of most scrutiny. Many scholars have determined the arched rib to be a primary structural component. Following my own research I concluded that Herland intended the roof's stability to depend largely on the hammer-beam framing, but with some belt-and-braces structural function built into the rib. After all, this was carpentry of previously unprecedented scale and aesthetic intent for the most demanding of clients, and for Herland to experiment with the untried framing of a structural arched rib in such a colossal roof seems unlikely. Literature: The literature on the Westminster Hall hammer-beam is extensive, beginning early in the nineteenth century. Good bibliographies are found in Courtenay (1984), Courtenay & Mark (1987), Beech (2015 and 2016) and this website.

Indispensable is Frank Baines’s Report … (1914).

|

|---|---|

| Wind Brace: | Timber set in the plane of the roof, usually between purlin and principal rafter, to create triangulation and thus prevent racking, viz the tendency of a series of roof frames to collapse like a domino rally. In certain parts of England and Wales, for example the western counties of England, wind bracing eventually became more about ornament than structural integrity. A fine example of ornamental wind bracing is at the Guesten Hall Curiously, up until around the second quarter of the thirteenth century, western European carpenters seemed unconcerned by racking, and even huge roofs were constructed with the complete absence of structural longitudinal timbers. For example, France, choir of Bayeux Cathedral, 1227-28; in England, Wells Cathedral, nave; 1212-1213; Lincoln Cathedral, St. Hugh's Choir roof, c.1201. Wind braces are difficult to identify in medieval documents, the term ‘wynde beam’ mainly applying to collars. Literature: Mercer (1975); Yeomans (2009); Hoffsummer (2009); Beech (2015).

|

| Woodlands | Awaiting entry |

|---|

| Wymondham Abbey | One of the finest medieval hammer-beam roofs. Another corker is in the north aisle. In the nave, form triumphs over function. The angel hammer beams extend well beyond the point where they serve any structural purpose, and the carpentry is essentially an elaborate arch-braced roof. Without tie-beams one suspects the steep pitch and wall parapets safeguard against lateral spread. An array of angels also adorns the cornice, and extravagant flower bosses terminate the king pendants and the intersection of principal and purlin. The floral bosses, extended hammer beams and king-pendant framing are reminiscent of Carbrooke Church 12 miles away, albeit there on a reduced scale. Was the same carpenter responsible for both roofs, with Carbrooke perhaps the practice piece? The north aisle hammer-beam is said to be late C15. |

|---|